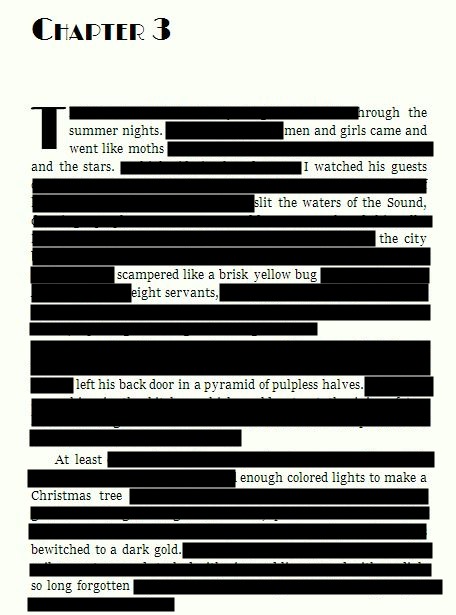

Here is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, erased, blacked out by a reader’s magic marker. She has kept what is useful to her, and done away with the rest. Some might call this gesture irreverent, disrespectful, or even destructive. But writers do the same thing every day. When crafting a story or a poem, one selects the elements of convention that are useful, discarding the rest. Every poem, every story, and every essay is a deconstruction (and revision, and erasure) of the work that came before it. We select the parts of convention we wish to preserve, and there’s nothing disrespectful about it. It’s merely the writer’s job.

Here is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, erased, blacked out by a reader’s magic marker. She has kept what is useful to her, and done away with the rest. Some might call this gesture irreverent, disrespectful, or even destructive. But writers do the same thing every day. When crafting a story or a poem, one selects the elements of convention that are useful, discarding the rest. Every poem, every story, and every essay is a deconstruction (and revision, and erasure) of the work that came before it. We select the parts of convention we wish to preserve, and there’s nothing disrespectful about it. It’s merely the writer’s job.

In my opinion, this erasure is useful for thinking about hybrid genre work for several reasons. First of all, you are selecting the aspects of genre convention that you wish to work with, and blacking out the rest. And even when working in hybrid forms, genre is still present in much the same way that Fitzgerald’s text is still visible beneath the black markings of the erasure. When we see a short story, for example, we expect a certain type of narrative arc. For the writer, these readerly expectations are material, knowledge you can use to surprise the reader and make them think. This is one of the primary goals of the course. Even when working in the most experimental modes, the ghosts of tradition, literary history, and genre convention will haunt your work. Just as the reader of the text shown above expected a pristine, unbroken narrative, your readers will come to your hybrid work with preconceived ideas about how stories unfold. In this class, we will work on using these readerly expectations to your advantage, making readers think, showing them new possibilities within received forms, and fostering more open-minded reading practices. Lastly, like the individual who erased Gatsby, you will select only the elements of tradition that are useful to you, forgetting the rest, or better yet, inventing the rest.

Hybrid Genre Writing: A Spectrum

Hybrid work can have elements of poetry, nonfiction, scholarship, fiction, or any combination thereof.

What does the term hybrid mean, exactly? For the purposes of this course, hybrid writing is any type of literary work that utilizes the resources of more than one traditional genre category. Here are some definitions and representative authors to help you get a sense of the range of hybrid genre work that exists in today’s literary landscape.

Lyrical Fiction: This term often refers to fiction (in novel or story form) that draws from the stylistic repertoire of poetry. Fiction that uses alliteration, assonance, consonance, and the repetition of sounds more generally, to create meaning. Fiction that relies on recurring imagistic motifs for structure and coherence, rather than narrative in the traditional sense. Lyrical prose frequently uses these poetic devices to heighten narrative suspense, and to elicit even more of an emotional response from the reader than the narrative itself could. The techniques of poetry supplement, create, and drive narrative in lyrical fiction. If you’re looking for some enjoyable examples available online, Carol Guess, Joanna Penn Cooper, Kelly Magee, Matt Bell and Molly Gaudry are a few well-known contemporary authors working in this tradition.

Lyric Essay: This term frequently refers to creative nonfiction that draws from the resources of poetry. Lyric essays, like creative nonfiction, draw their inspiration from the events of real life. But, like lyrical fiction, they frequently use the stylistic devices of poetry to elicit an emotional response from the reader. The lyric essay tradition is rich with imagistic motifs, fragmentation, and recursive narrative structures. The story folds in on itself, returning to images, ideas, and language from earlier in the text, often in a different context. Much like poetry, the lyric essay takes the imagery surrounding an experience (think of everyday objects, love tokens, mementos…), then inscribes it and reinscribes it with myriad possibilities for interpretation. Meaning accumulates, gathering around the detritus of a past experience. Unlike conventional prose works, which have a linear structure, lyric essays will circle around the same object or experience, which gains significance with each tangential orbit. Some contemporary practitioners of lyric essay include Maggie Nelson, Julie Marie Wade, and Eula Biss. If you’re interested, all three writers have work freely available online.

Creative Literary Criticism: There’s a great deal of hybrid genre work that questions the boundaries between “critical” and “creative” writing. After all, these distinctions seem arbitrary, and reflect larger power structures within the literary community and in the academy. Those in power decide what can be counted as “scholarship.” Perhaps the best known example of this type of writing is Jenny Boully’s The Body: An Essay, which we’ll look at later in the course. In this collection, Boully takes an academic form of writing (footnotes) and fills it with content that doesn’t seem academic at first glance: personal narratives, aestheticized language, and even descriptions of dreams. By using form in such a way, Boully calls our attention to the artificiality of the categories that we impose upon language. Indeed, personal experience, beauty, and the unconscious mind call all be brought to bear on theoretical debates. Other practictioners of creative scholarship include Kristy Bowen, Thalia Field, Spring Ulmer, and Carla Harryman.

Reading Assignments | Types of Hybridity

Lyrical Fiction

G.C. Waldrep, “Stigmatic Affection”

Richard Siken, “War of the Foxes”

Matt Bell, “The Girl in the Golden Hood”

Lyric Essay

Eula Biss, The Balloonists

Creative Literary Criticism

Kristy Bowen, “algorithms” and “footnotes to a history of

desire”

Writing Assignment | Erasing (or Inventing) Genre

Begin by choosing a form of writing that’s decidedly uncreative. This can be anything, from an advertisement to a footnote. Here are a few possibilities:

• Footnotes to a Book of Your Choosing

• A Glossary

• Endnotes

• An Appendix

• Job Listing

• Job Application Letter

• Conference Presentation

• Abstract for a Scholarly Paper

• An Encyclopedia Entry

• An Advertisement

• An Etiquette Guidebook

• A Travel Guide

Choose any form that interests you, but it should be a form of writing that readers expect to be practical. A type of writing that usually does its job, nothing less, nothing more.

Prompt & Example

Once you’ve chosen your form, make a list of elements that a reader will expect to find. For example, if you’ve chosen “Job Application Letter,” you know a reader would expect to find a list of credentials, an applicant’s name, his or her contact information, and perhaps some information on how the writer meets the qualifications of the job. After you’ve considered the components of this type of writing, decide which ones to keep, and choose which ones to discard. For the Job Application Letter, you might keep the letter format, but not include the applicant’s credentials. Once some of the elements of the genre have been discarded, think about what you will put in their place. For this assignment, I’d like you to insert some unexpected element (whether it’s content, sound, imagery, fragmentation, unconventional grammar, etc.) into this practical form of writing that you’ve chosen. Consider carefully what the reader will expect, and what they won’t expect. How can you use what’s familiar to surprise them?

Here’s an example: Robert Miltner’s “Hope is a Feathered Thing”

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of eighteen books, which include VOW, PETRARCHAN, and SCORCHED ALTAR: SELECTED POEMS AND STORIES, 2007-2014, which is forthcoming from BlazeVOX Books. Her writing has been described by literary critics as “haunting,” “mesmerizing,” and “complex.” Poet and Kenyon Review editor Zach Savich writes that her body of work is a “singularly graceful and stunningly incisive exploration of poetic insight, vision, and transformation.”

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of eighteen books, which include VOW, PETRARCHAN, and SCORCHED ALTAR: SELECTED POEMS AND STORIES, 2007-2014, which is forthcoming from BlazeVOX Books. Her writing has been described by literary critics as “haunting,” “mesmerizing,” and “complex.” Poet and Kenyon Review editor Zach Savich writes that her body of work is a “singularly graceful and stunningly incisive exploration of poetic insight, vision, and transformation.”