I have a gay ankle. That is not a typo. It is not supposed to read as “I have a gay uncle.” I don’t even have an uncle. So, no, there is no gay uncle. But my ankle is very, very gay.

I have a gay ankle. That is not a typo. It is not supposed to read as “I have a gay uncle.” I don’t even have an uncle. So, no, there is no gay uncle. But my ankle is very, very gay.

How this happened: I’m seventeen and know, like really know, that I am a lesbian. It’s just one those things you know. And so in order to confirm my sexuality I find a woman to date. She’s not that attractive. She’s not that smart. Her sense of humor is weird. She’s a cowgirl and I don’t know anything about horses or barns or farm animals or any of that. But she’s got an essential element to her that is what makes me want to date her. She has a vagina. This is my only standard for people whom I want to date when I’m seventeen. Congrats vagina-totin’ cowgirl, you meet the requirement to be my girlfriend.

First girlfriend cowgirl is a big dyke with a shaved head and Wranglers sucking onto her legs and a dingy white t-shirt that is always smeared with things found in a barn. She is my first girlfriend. She is my Cowgirl Dyke.

Upon dating Cowgirl Dyke, though, I realize I need something more than her pussy that I lick in order to confirm to me that I really am gay. I need something on my body that shouts my sexuality to the world, some daring thing that declares that I am, always have been, and will forever be a dyke.

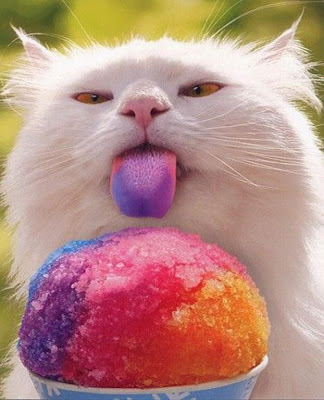

I get an upside down rainbow-colored triangle tattooed on my ankle.

And because I’m seventeen when I want this tattoo, I present Cowgirl Dyke’s driver’s license (because she’s eighteen) to the tattoo artist in order to hopefully dupe him into believing that I am old enough to get this tattoo. I look nothing like Cowgirl Dyke, and I know the tattoo artist is not fooled by this ID. But I can tell from the big sigh that erupts from his lips and his dramatic shrug of the shoulders as he looks at the ID that he just doesn’t have the heart to turn down this baby dyke’s request for a gay pride tattoo. She looks so desperate, so obviously in need of something to confirm her sexuality.

I get the tattoo. It will be the first of twelve tattoos I get in the next twelve years.

So this is it. I am permanently stamped as a lesbian. I have a gay ankle. A part of my skin will forever prove to the world that I am gay.

I am branded, like one of Cowgirl Dyke’s cows.

Funny story: twelve years later and I’m the beautiful gushing bride to my beautiful boy husband. I didn’t think boys could be beautiful. And I never thought that what was between a person’s legs would not be important to me one day, because here is a person that I love regardless of his gender and I don’t need to confirm and/or explain my sexual orientation to anyone. I am me, a lesbian who is married to a man. Some would call me a hasbian. Some would call me straight, bisexual, undecided, whatever dumb label one feels as if s/he has to put upon a person who goes through a little sexuality shift.

And while I may not identify as an absolute, never-going-to-be in-a-relationship-with-a-man, because hell no women-are-for-me gold star kind of a dyke, I do still have that gay ankle that reminds me of what was important to me at one point in my life. Just like how when I was nineteen I just had to get that tattoo of the sun and moon on my lower stomach because I thought I would forever be a hippie Wiccan, and like how at twenty I just had to get that tattoo of an owl on my shoulder because I wanted the world to think I wise. Identities change. Because now I’m an atheist who takes pride in the fact that there are many things in life I know nothing about.

I am tatted up and while my current self really doesn’t need that om sign on my foot, it, like all of my tattoos, is a mile marker for what was most important to me at one point in my life. Big gay ankle. A wise bird on my shoulder. Hippie-Wiccan art on my stomach.

All of this is to say that while I may have out-grown the desperate need to confirm my sexual orientation by branding a gay pride symbol on my ankle, that part of my life will never leave me. Because even with this husband dude in my life, I still think of myself as a big dyke, as someone who takes pride in her sexuality—whatever that might be.

Chelsey Clammer received her MA in Women’s Studies from Loyola University Chicago. She has been published in THIS, The Rumpus, Atticus Review, Sleet, The Coachella Review and Make/shift among many others. She received the Nonfiction Editor’s Pick Award 2012 from both Revolution House and Cobalt, as well as a Pushcart Prize nomination. Clammer is a weekly columnist for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, as well as the assistant nonfiction editor for both Eckleburg and The Dying Goose. She is currently finishing up a collection of essays about finding the concept of home in the body, as well as a memoir about sexuality and mental illness. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.