I.

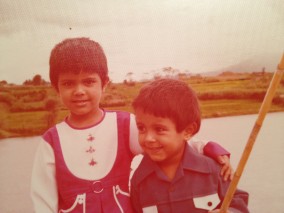

It is 2014. Blue, flowing water glides into my memory. The Bagmati River is healthy and calm behind my brother and me. It was perhaps 1977, when my brother was about four or five and I was five or six years old. We stand arm in arm in our thick crepe polyester outfits (me in a red and white top with matching red pants; my brother in a blue and white top with matching blue pants), smiling at the camera, our mother. In this picture, we’re standing next to each other on a roadside. Slightly hidden behind my brother is a white milepost that rises from the earthy bluff by the river somewhere between our home in Kirtipur, and where a tributary of the Bagmati River—the Balkhu River—flowed circuitously in Sanepa. Behind the river is a lushly verdant, pastoral landscape that is now overrun with concrete buildings. We look so innocent, so young, so nestled in the scenery around us. We belonged and we look it – it’s in our smiles and in the way we stood: my brother leans against me, bamboo stick in his hand as my left arm drapes around him, securely holding him close to me, so close that there is barely any space between our bodies. He stands, smiling but looking away from our mother. Where he is looking is off to my right, to some place that exists past the picture’s edge. And while we are standing, posed, his glance to that other direction makes him look as if he is about to run off and play with his bamboo stick, with whatever is competing for his attention. And yet, even with a good number of distractions that surround us and that we want to adventurously leap towards, in the picture, we look shy. We are posing, after all, and it is possible our mother even instructed us to look sincere and not goofy or solemn as we are in many of our pictures. Whatever it was, it worked. We look cherubic.

Some thirty years later, I hold that photo in my hands and am jarred by its stark reminder: there was a time when I was once taller than my brother; there was a time when the full Bagmati occasionally rose even higher. I am no longer taller than my brother. The Bagmati does not flow. Instead of a swollen river, now there’s a long and winding sand lot where trash gathers, animals and people defecate, and encroaching concrete houses claim a part of the earth that at one time only ever saw fish. Like the two innocents who posed in front of the Bagmati, the river has aged, its young waters also a memory. When I last visited this section of Kathmandu, I couldn’t locate the scene in that picture. It no longer exists.

II.

It is 1980. My brother and I leave with my father for the United States. My mother is already there, studying for her PhD in Anthropology. My brother and I don’t want to leave; we have friends and relatives in Kathmandu and throughout Nepal and now we won’t be seeing them so often. But, my parents need us elsewhere, need us with them.

We stay in my mother’s one-room apartment for a month. She lives in a graduate student dormitory. We have to share the kitchen and bathroom with her fellow students. My brother and I take the month to acculturate to the United States, while my father looks for work. He seeks out the help of a headhunter and my mother goes to class. My brother and I spend the days learning English from soap operas. We drink a glass of cold milk. Then we drink glass after glass after glass of cold milk. We’ve never tasted it before. I take long hot showers. I learn that I don’t like taking baths: the water just slowly cools, and my body finds no comfort in that. Hot water that flows freely from the showerhead is a luxury. In Kathmandu, we had to first boil the water and then bring the hot pot of it to the tub so we could bathe.

There is an outdoor pool on my mother’s dormitory grounds. It’s open to graduate students and their families. My father enjoys swimming and commits himself to teaching us that same love. I’m twelve when I learn how to swim. My brother is ten. Maybe it’s because we were so late in our youth when we learned to swim that my brother will grow up with distaste for swimming, for just being in the water, actually. But he will take his future daughter to frolic in the ocean near where they will live. For many years, I too will dislike swimming. It will be something about vanity, something about feeling shy while wearing a bathing suit. But mostly, it will be about feeling uneasy in the water, that it could consume me whole.

III.

It is the summer of 1991. I’ve just finished my first year of college and my brother is about to become a senior in high school. We travel to Kathmandu. We are without our parents and are visiting Nepal for the first time since our departure. I’m 19, which makes my brother 17. We are a decade older than when we left. I know some Nepali, more than my brother. But we both understand our mother tongue when we hear it. We stay about a month.

In that month, we connect with grandparents, with old and new aunts and uncles, with nieces and nephews. But in that month, we are cherished as a novelty. People ask my brother about his origins when he walks around Kathmandu in shorts and a t-shirt. They don’t believe he’s from here. And so he feels alienated from his own countrymen. I am no help to my brother. I cry wherever I go, mourn the loss of what was and what will never be again. My brother and I are strangers. We are strangers in our own family. And our homeland is a stranger to us. It has changed. We were heartbroken.

Bagmati is nearly dry. The water that should be flowing is competing with mounds of human waste and people trying to take ownership of any land, even if it belongs to the river. What little water that does flow, especially after a rainfall, is compromised for drinking and bathing and rituals. Yet, in a city like Kathmandu where the water table is also drying, residents who rely on the river hold their faith in it, even as it continues to disappear because the carpet industry keeps recklessly tapping it. So, my brother and I also put our faith in the river, though it no longer flows. We want our homeland as we knew it. We want to be a part of our family as we knew it. We leave with pictures of dear family members and phone numbers and promises to return. On the tarmac, I hold my brother while he cries with more pain than I have or will ever see him express. And then, our plane takes us away from Kathmandu.

IV.

It is the summer of 2010. I join a gym for its pool. I’m not quite sure what’s motivating me. For about the next year, I try but cannot completely quench my inexplicable longing to be submerged in the water. Submerged as if I am trying to get somewhere spiritually in that blue depth. It is my habit to not rise early, but here I find myself waking up at 6 a.m. to go swimming. I feel euphoric and at ease with my body, all because I’m moving through water. The silence under water is so peaceful. And, I will return to that pool again and again, getting that spiritual sense each time. But then I will throw my back out. And then a few months of healing will go by. And then I will go back to the pool, but will suddenly be afraid of its depth. I could drown. This one thought will completely overwhelm me. I do not try to swim again. I stay on the ground, gazing at what scares me.

V.

It is 2014. Here we are. We never received letters from our family overseas, though we wrote. We haven’t returned to Kathmandu together. Nor has the water to the Bagmati. And yet I drown. I drown in the dream of never knowing what it’s like to leave home, to leave family.

Now, I am holding that picture and I see three extinct innocents looking up at me: two siblings at ease in their homeland, and a river behind them, blue and fulfilling in its flow.

Vipra Ghimire is a student of writing at the Johns Hopkins University. She has an MPH, and her interests in writing and health care range in topics from animal rights to civil liberties to disease. Born in Kathmandu, Nepal, she’s lived in the US since 1980. The vast world sometimes frightens her. However, she laughs easily and has been known to say and do many nonsensical things.