“In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.” Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

“In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.” Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Most misunderstandings in human history could have been avoided if somebody had just kept their pen dry and their mouth shut. But writers simply can’t do that. History reminds us that most revolutions have been triggered by bloggers, texters, and leftist op-ed columnists. Their populist rabblerousing backfired on many when the old guard retaliated or sociopaths usurped their utopias.

Literary decapitation enjoyed a comeback during the French Revolution. The first casualty, Jean-Paul Marat, an MD with herpes, began his writing career with a dissertation on gonorrhea. Then he made a seamless transition to politics. Of the royal pox afflicting the masses, the doctor wrote in his newspaper, L’Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People), “Perhaps we will have to cut off five or six thousand; but even if we need to cut off twenty thousand, there is no time for hesitation.”

Marat declared that the patriotic writer must also be ready for “a miserable death on the scaffold.” He explained: “I beg my reader’s forgiveness if I tell them about myself today…. The enemies of liberty never cease to denigrate me and present me as a lunatic, a dreamer and madman, or monster who delights only in destruction.” But, in the end, Marat didn’t find himself in his colleague Dr. Guillotine’s apparatus, but in his own bathtub, bloody pen in hand and Charlotte Corday’s kitchen knife in his chest.

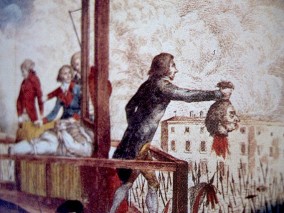

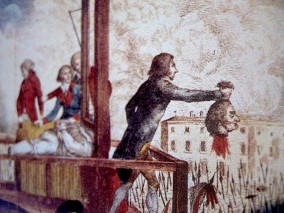

A year later, Robespierre, another Revolution staff writer, found himself under the National Razor in spite of having been deified at his Festival of the Supreme Being only weeks before. “Look at the bugger,” another journalist gasped, “it’s not enough for him to be master, he has to be God!”[1] Indeed, the “Incorruptible” had always delighted in the beheadings of his colleagues. The last had been the proud Danton whose last words to his executioner — spoken like true Frenchman in anticipation of the unbearable lightness of being — were: “Don’t forget to show my head to the people. It’s well worth seeing.”

Things went south for Robespierre at the next death panel party of his writer’s group, The Committee of Public Safety. When the other members demanded justification for Danton’s execution, Robespierre found himself at a loss for words. “The blood of Danton chokes him!” cried his colleagues. Smelling the coffee, Robespierre excused himself to the men’s room of a next-door hotel. When the gendarmes arrived, the Reign of Terror writer shot himself in the jaw. The next morning, the Incorruptible, age 36, was guillotined — face up.

This was a sunny day indeed for the Marquis de Sade. The year before, 1793, Robespierre had sent him upriver for writing a eulogy of his friend, Marat who, with Voltaire, had enjoyed his countryhouse orgies. The Father of Sadism had first entered the French Pen Program back in ’77 over a lewd and lascivious beef involving livestock and underage kids. During a second stretch in the Bastille in ’84, the count spent 37 days completing his magnum opus, 120 Days in Sodom, on a 12-meter roll of paper (much as another outlaw, Jack Kerouac, would use 200 years later for his own licentious masterpiece, On the Road). The novel earned its author an immediate transfer to Charenton insane asylum. On arrival at the stately nuthouse, the sadist experienced the most intolerable pain of his life: his manuscript had been confiscated. So he put his nose to the grindstone and rewrote Sodom. Then, he pressed on to complete his next title, Justine, about the rape and torture of an ingénue, later electrocuted by lightening. Finding this “the most abominable book ever engendered by the most depraved imagination,” Napoleon torched it and threw the degenerate back in prison, this time for the rest of his unnatural life.

A century and a half later, petty thief and pederast, Jean Genet, was penning his own homoerotic tour de force, Our Lady of the Flowers, on prison grocery bags. When the guards burned the kleptomaniac’s masturbation fantasy, the irrepressible con — outdoing the Sade himself — not only cranked out a new, improved copy, but four more novels, three plays, and a host of love couplets. So impressed were Sartre[2], Cocteau, Picasso and others with the high school drop-out’s output that they successfully petitioned the French premiere for his release. Hardly was he paroled, however, than Genet experienced writer’s block. On numerous occasions, he tried to get himself re-arrested in order to continue with his literary and his love life. But, as a free man, further masterpieces proved beyond his grasp, and he whiled away the rest of his days with a suicidal tightrope walker, then with the Black Panthers and Palestinians.

[1] David Andress, The Terror (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007)

[2] Sartre himself did time in a German POW camp. Here he wrote a Christmas play, and digested the entirety of Heidegger’s Being and Time, a feat rarely accomplished by anyone outside of prison. Years later, The Existentialist philosopher nearly went up river again on a Civil Disobedience beef, but was pardoned by the history-challenged President Charles de Gaulle who declared, “You don’t arrest Voltaire!”