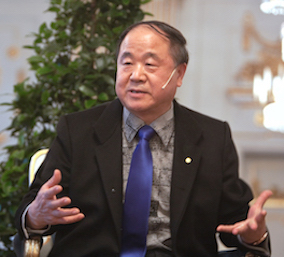

Mo Yan was born 17 February 1955

Little known fact

Guan Moye finally adopted his pseudonym as his official name after having difficulty claiming his royalties because of the convoluted administrative process in place while still serving in the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA). (Wang)

Much better-known fact

Mo Yan, Wade-Giles Romanization Mo Yen, was a pen name for Guan Moye and it means “don’t speak,” an admonishment from his parents in rural China many years ago.

Guan Moye grew up in Shandong province in northeastern China where he left school to become an agricultural worker and a factory worker during the Cultural Revolution. He enlisted in thePLA and ultimately became an officer. While serving, he became educated through self-study and an assignment to a PLA institute where he began to write. Using the pseudonym Mo Yan, he became a novelist and short-story writer known for his imaginative and humanistic fiction—not always with the warm approval from Chinese leadership, particularly while he was still serving in uniform. His work found popular acclaim and awards starting in the 1980s. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, the first citizen of the People’s Republic of China to do so.

Early life and career

Guan Moye’s parents were farmers in a poverty-stricken village in the People’s Republic of China—very much like the fictional Gaomi County in his fiction. It was there with his family that he survived the Great Famine of 1958-61. During the end of the turbulence of the Cultural Revolution of 1956-66, he left school in the fifth grade to work in agriculture and later in a factory. In 1976, he joined the PLA to escape the isolation and poverty of the province. In Change, described as a novella posing as an autobiography, he describes several unfulfilling assignments as an enlisted man. However, he showed enough promise that when his unit is given a quota for a test for entry into a PLA institute of higher learning, he was given the opportunity. The unit’s quota was lost toward the end of his six months of self-study before he could stand for the testing, but his enhanced knowledge led to his being appointed during an army-wide push to increase literacy as a military base mathematics instructor and later as a political instructor—both positions normally filled by officers. In 1982, he accepted a commission as an officer and did get another opportunity to take the admission test. As a result, he earned an appointment to the Literature Department of the PLA’s Arts College, from which he graduated in 1986. During that time of intense study, he found initial success in publishing his work. He was well known as an author by the time he was invited to attend Beijing Normal University for a Master of Literature and Art, awarded in 1991. He left the army in 1997 and became a newspaper editor, continuing to write fiction, still drawing on his rural hometown to create his imagined setting and his vibrant characters warring, loving, and enduring the crushing experiences of his formative years.

Major relationships

In 1979, he got permission from his superiors to go home on leave for a few days, get married, and return to his unit alone. Under those constrained conditions, he married Du Quinlan, and they celebrated the birth of a daughter in 1981.

Writing career

In Change, Mo Yan recalls several failed attempts to publish his writing: a short story “Mama” and a six-act play Divorce. His first published short story, a “Rainy Spring Night,” appeared in Baoding literary journal Lily Pond in 1981, followed the next year by “The Ugly Soldier.”

In 1984, the year he entered PLA’s Arts College, he earned a literary award from the PLA Magazine, adopted the pseudonym Mo Yan, and published his first novella, A Transparent Radish.

In 1986, Red Sorghum won the national best novella award, becoming an internationally known film the next year. This sequence launched Mo Yan’s career as a writer as well as the careers of the film’s director Zhang Yimou and the lead actress Gong Li.

Since then, Mo Yan has published more than a dozen novels and has received every major national literary award China has to offer. In the process, he has had works pulled off the shelf and banned more than once because of his satirical treatment of Chinese institutions and historical movements—seen through the eyes and experiences of the people rather than the makers and implementers of policy.

Mo Yan writes about the gut-level aggression and bravery of peasants against Japanese soldiers, against both sides of the Chinese Revolution, the Great Leap Forward’s forced migrations and collectivization, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath—through oral traditions, histories, and personal observances. He portrays the violent vitality of men engaged in war and sex, and he elevates the resilience and forbearance of the women he has seen in these histories. The women are extolled for their determined and creative drives to endure their lot (exploited and taken for granted) while the men drink, love, and fight single-mindedly. Critics note that in most of his novels, “a blunt and unrelenting masculinity…serves as a stark contrast to the usual tame and sexually repressed heroes of the proletarian literature of previous generations.”

In his writing on these social and economic themes within their historical contexts, Mo Yan draws on his determinative experiences and on settings in the county-level city of Gaomi in eastern Shandong province. He has lived in, endured, and escaped rural isolation and famine. He has witnessed and lived with the legacy of grim decisions made by common people under duress.

The Nobel Committee’s “Bio Notes” describe his work as a “mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives.” His work, they say, is “reminiscent in its complexity of those in the writings of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez.” Mo Yan would agree to having been influenced by those two icons, but several critics declare his voice is quite distinct from those voices. The Notes go on to allude to “a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition,” a claim that some scholars like Sun take great exception to as discussed below.

Mo Yan’s Change is clearly an example of a “people’s history.” He provides us with a bottom-up lens rather than a top-down one of a country in stormy fluctuation. As his writing evolved, he experimented with his narration to the extent he cast himself as a character in one of his novels like Vonnegut. “All his novels create unique individual realities, quite different from the political stories that were told about the countryside in the Maoist years, when Mo Yan grew up” as Guan Moye. (Flood)

In fact, he draws in the reader to actively consider which of the many cataclysmic events the characters are surviving because no labels are put on movements or political platforms or even wars; it is very much the way common people in remote areas view these events that bring armed men into their areas and other men and women to recruit local men and women to the point that relatives are reluctantly coercing and bullying one another when they get the upper hand. And then there are those—in the usual point of view of a closely observed Mo Yan character—who are avoiding taking sides and suffering at the hands of those with weapons.

Mo Yan provides his readership of the novel Big Breasts and Wide Hips with reminders of the propagule pressure on rural families to produce male offspring—to the point of uncles discretely (at the urging of their own wives) providing services as active sperm donors for the wives of sterile nephews. He gives us a view of the Japanese invasion in the 1930s and the warring between the Nationalists and the Maoists through the eyes of a small boy without ever using the labels of those events—conveying a truly surreal and violent drama not understood at all by the rural Chinese. He delivers the horrific unintended consequences of agrarian and industrial policy like the Great Leap Forward—consequences he survived as his family struggled through the Chinese Famine.

He treats social decrees like the One Child policy developed later in hauntingly personal prose in Frog where he draws a portrait of an agonized world of “desperate families, illegal surrogates, forced abortions, and the guilt of those who must enforce the policy.”

Mo Yan says he has been greatly influenced by a broad spectrum of writers such as William Faulkner (Nobel 1949), James Joyce, Gabriel García Márquez (Nobel 1982), Minakami Tsutomu, Mishima Yukio, and Ōe Kenzaburō (Nobel 1994).

Critical look at controversies and aesthetics

The Chinese government warmly received the news of the Nobel Prize award, mentioning Chinese writers and the Chinese people have been waiting for such recognition for far too many years.

Then the criticism began. There were those writers and dissidents who criticized his lack of solidarity with other intellectuals who were continually denied freedom of expression in the Peoples Republic. These comments were echoed by European literati like 2009 Nobel Laureate Herta Müller who grew up and wrote under the Communist regime in Romania. (Maslin and En Khong)

En Khong criticizes Mo Yan for dealing with China’s troubles at the local level and indicates this focus shows Mo Yan’s alignment with state strategy for the allocation of blame away from the political center.

Charles Laughlin, a professor of Chinese Literature at the University of Virginia, published “What Mo Yan’s Detractors Get Wrong” on ChinaFile to take on the early disparagers reproving Mo Yan of what they asserted was trivialization of grave historical calamities through the use of black humor and amusement. Laughlin maintained that Mo Yan’s intended readers already knew that “the Great Leap Forward led to a catastrophic famine, and any artistic approach to historical trauma is inflected or refracted. Mo Yan writes about the period he writes about because they were traumatic, not because they were hilarious,” he declared.

“The effect of Mo Yan’s work is not illumination through skilled and controlled exploitation, but disorientation and frustration due to his lack of coherent aesthetic consideration. There is no light shining on the chaotic reality of Mo Yan’s hallucinatory world.” This is the way Anna Sun, Associate Professor of Sociology at Kenyon College, starts out her blistering critique. She declares Mo Yan’s writing as coarse, predictable, and lacking in aesthetic conviction. “Mo Yan’s language is striking indeed,” she writes, but it is striking because “it is diseased. The disease is caused by the conscious renunciation of China’s cultural past at the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.”

However, if one reads her whole critique, it becomes clear her real discontent lies in Mo Yan’s use of language and his failure (due to, she admits, the fact he was denied access given the time of his birth and formation) to acknowledge through emulation and cultural reference the two thousand years of Chinese Literature that preceded Mao.

Regardless of the sincerity of Mo’s social and political critique, Sun sees his language as a language that survived the Cultural Revolution, when the state implemented a radical break with its own literary past. “Mo Yan’s prose is an example of a prevailing disease that has been plaguing writers who came of age in what can be called the era of ‘Mao-ti,’ a particular language and sensibility of writing promoted by Mao in the beginning of the revolution.” (Sun)

The burden of this heritage can be seen not only in Mo Yan’s work, but also in the work of many other revered literary writers—even political dissident writers outside of China like the novelist Ma Jian. “This is perhaps the ultimate tragedy of the fate of contemporary Chinese writers: too many of them can no longer speak truth to power in a language free of the scars of the revolution itself.” (Sun)

There are some critics who recognize that the need for obliqueness under difficult circumstances can also make the case (that Mo tries to make in his own defense) that literary imagination can become more resourceful under stressful conditions.

“Such is the case with Mo Yan’s deeply interesting fiction,” says Mishra. However, Mo Yan’s writing is rarely discussed because of the political choices he has had to make. The West is very uneven in the standards they apply to writers’ politics. While Mo’s choices can be considered shameful, that level of scrutiny is not applied to his counterparts in the West. (Mishra)

Professor Laughlin offers a comprehensive analysis of Sun’s article about what is artistically wrong with Mo Yan’s fiction and, therefore why, in her mind, it does not deserve the Nobel Prize in Literature. He notes that Sun does not describe or interpret specific works by Mo Yan, though she declares that his main translator, Howard Goldblatt, creates translations of Mo Yan’s work that are artistically superior to the originals. He also points out that Sun does not identify any other deserving Chinese writers and that, by her argument, it is not clear that the prize should ever go to a Chinese writer. (Laughlin)

The “mostly devoid of aesthetic value” assertion by Sun doesn’t obtain for long, as the literature professor points out, the history of the world and its literature have departed from the moral certainty of Dickens some time ago. Laughlin, the scholar of literature, schools the sociologist about how the emergence of avant-garde techniques like stream of consciousness or psychological realism in the wake of World War I (Mann, Woolf, and Joyce) provided a means of coping with historical trauma. He points to of the absurdism of a Kafka, Orwell, and Borges as alternative ways to deal with the ghosts of socialism, bureaucracy, and alienation since then. (Laughlin)

Finally, Laughlin notes that Mo Yan “grew up in cruel times and at times treated people with cruelty, only reflecting on or regretting it much later, too late for his remorse to remedy the damage.” It is apparent in the reaction to Mo Yan’s award that we want Nobel laureates born in repressive societies to be heroes. However, Laughlin points out, the appearance of heroism often disguises human frailty and even cruelty. And, if artistic expression of that reality “requires courage, it also requires honesty, it requires being painfully honest, and such honesty is not beyond the reach of contemporary Chinese literature.”

Magical realism and hallucinatory realism

Magic realism can prompt readers to connect more intensely humanistic and sociopolitical realities than realist fiction—perhaps because the introduction of ambiguity pushes the reader into an active process of turning over the ambiguity to resolve it based on individual experience and education.

Hallucinatory realism has links to the concept of magical realism. Hallucinatory realism connotes a notion of a dream state, and that was the term used in the explanation for awarding Mo Yan the Nobel Prize in Literature. Certainly, there are moments in Mo Yan’s narratives such as Large Breasts and Wide Hips where the narrator’s descriptions take up the reader into the distortions of the moment’s visual or tactile experience, often to be brought down harshly by the reality of the situation—along with the narrator who is experiencing violence up close and personally.

In this brand of magical realism, there is not so much turning a perception over and over (as in Western minimalist exaggeration) as it is a turning once over to consider the age and experience of the character perceiving the distortion and to nod at the briefness of the momentary escape from the reality of a grim moment.

A few quotes of Mo Yan

“I saw the winner of the prize both garlanded with flowers and besieged by stone-throwers and mudslingers.” He concluded, “For a writer, the best way to speak is by writing. You will find everything I need to say in my works. Speech is carried off by the wind; the written word can never be obliterated.”

“Why did a novel about the Sino-Japanese war have such a great impact on society? I think my novel expressed a shared mentality of Chinese people at the time, after a long period of repression of personal freedom. Red Sorghum represents the liberation of individual spirits: daring to speak, daring to think, daring to act.”

A few quotes about Mo Yan

“If China has a Kafka, it may be Mo Yan. Like Kafka, Yan has the ability to examine his society through a variety of lenses, creating fanciful, Metamorphosis-like transformations or evoking the numbing bureaucracy and casual cruelty of modern governments.” — Publishers Weekly, on Shifu: You’ll Do Anything for a Laugh

“Red Sorghum represents a new articulation of the Chinese national spirit, a cry for the liberation of libido” — Anna Sun.

Mo Yan is “probably the most translated living Chinese writer, very well known, very respected [and] although he’s had his spats with the literary censors … generally speaking not regarded as politically sensitive” — SOAS professor of Chinese Michel Hockx (Flood)

Awards, Prizes, and Nominations (selected)

2005: Kiriyama Prize, Notable Books, Big Breasts and Wide Hips

2005: Doctor of Letters, Open University of Hong Kong

2006: Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize XVII

2007: Man Asian Literary Prize, nominee, Big Breasts and Wide Hips

2009: Newman Prize for Chinese Literature, winner, Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out

2010: Honorary Fellow, Modern Language Association

2011: Mao Dun Literature Prize, winner, Frog

2012: Nobel Prize

Notable Works

Red Sorghum (1986, English 1993)

The Garlic Ballads (1988, English in 1995)

The Republic of Wine (1992, English 2000)

Big Breasts and Wide Hips (1996, English 2004)

Shifu, You’ll Do Anything for a Laugh (2000)

Life and Death are Wearing Me Out (2006, English 2008)

Sandalwood Death (2004, English 2013)

Wa (Frog) (2009, French 2011, English 2014)

Sources

Bio NOTES Nobelprize.org.

En Khong. “Nobel winner Mo Yan and China’s cultural amnesia: The Nobel laureate’s comments on literary censorship were unforgivable,” The Telegraph 7:00AM GMT 14 Dec 2012.

Flood, Alison. “Mo Yan wins Nobel Prize in literature 2012: Novelist, the first ever Chinese literature Nobel laureate, praised for ‘hallucinatory realism,’ ”The Guardian Thursday 11 October 2012 07.38 EDT mod Wednesday 4 June 2014 00.21 EDT.

Laughlin, Charles. “Why Critics of Chinese Nobel Prize-Winner Mo Yan Are Just Plain Wrong,” ChinaFile December 12th, 2012. Web. 21 February 2016.

Mishra, Pankaj. “Why Salman Rushdie should pause before condemning Mo Yan on censorship: The Nobel laureate’s political choices are deplorable, but why don’t we expose western novelists to the same scrutiny?” The Guardian Thursday 13 December 2012 08.30 EST; last modified on Friday 15 January 2016 13.34 EST.

Mo, Yan. Big Breasts & Wide Hips. Translated by Howard Goldblatt. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1996.

Mo, Yan. Change. Translated by Howard Goldblatt. London: Seagull Books, 2012.

Sun, Anna. “The Diseased Language of Mo Yan,” Kenyon Review OnLine

Talks At The Yenan Forum On Literature and Art May 1942. Marxists Internet Archive. Internet encyclopedia project Web. 10 February 2016.

Wang, David interview. ChinaX: Introducing Mo Yan SW12X Uploaded on Feb 18, 2015. Wood, James. “Tell me how does it feel? US novelists must now abandon social and theoretical glitter,” The Guardian, October 5, 2001 5 October 2001 20.05 EDT Modified 5 January 2010 12.09 EST.

Richard Perkins is a regular contributor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review, and he is working on a historical novel and a collection of stories. He lives with his wife in Northern Virginia.